The one argument I can pose against renewables as the backbone of our energy grid is that they aren’t… well consistently reliable. You can have as many solar panels as you want. They can cover your roof and yard. Yet, without sunlight they won’t do you any good. Wind turbines are great until there is no wind. We cannot control the weather and at times the sun will shine and we can harness excess energy to the full capacity of our solar panels, but the sun shining today has little influence on if I need to charge my laptop tomorrow, or if I’m going to want to watch TV next winter. We need to bridge the gap between when we capture the abundant renewable energy around us and when we want to use it. The obvious answer here is batteries. So, let’s look at the how we store renewable energy today.

The largest store of renewable energy in the US is currently dams. Unlike a wind turbine of solar panel that needs the appropriate weather conditions to generate energy, a dam can store its energy producing resource, water, and then release the water to rotate its turbines as the need for energy arises. As of 2020 the US has 22 gigawatts of energy stored in dams. Unfortunately, this is the majority of our renewable energy storage capacity, with only an additional gigawatt of storage capacity in batteries. On a global scale, the International Renewable Energy Agency’s (IRENA’s) study on renewable energy storage is optimistic and the forecast is driven by declining costs. Per the IRENA, by 2030 total costs for installed battery systems could fall anywhere between 50-60% with prices reaching as low as $200 per kilowatt hour of energy storage. Though this is promising and exciting, this cost may still be a barrier to entry for many as the average price of a kilowatt hour in the US is only 13.31 cents. For a frame of reference, a kilowatt hour is sufficient energy to make 200 smoothies. So, in order to pay off each kilowatt hour battery, you would need to make 300,526 smoothies…

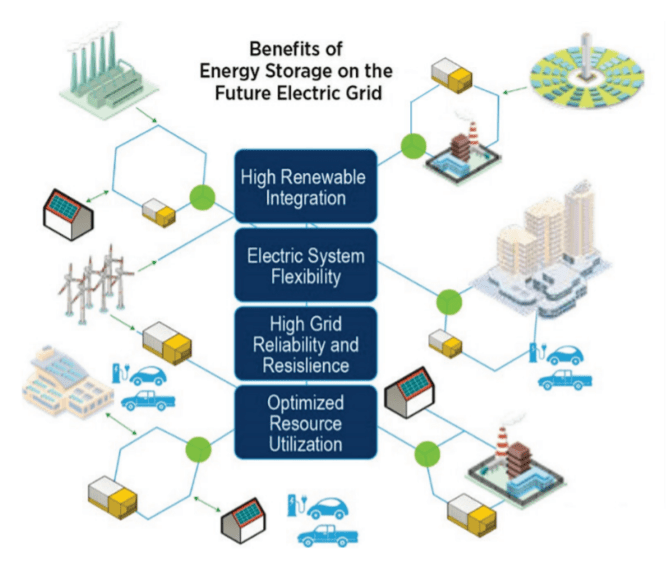

We may be a ways-off of large-scale adoption of battery systems at home, but what about utility scale adoption? Well as of today, we don’t quite have a solution for utility scale adoption but that doesn’t mean that we aren’t striving towards it. Here is a report by the U.S. Department of Energy highlighting over 30 research teams that are working on innovative ways to tackle our energy storage woes. These research topics range from improving existing technologies such as the architecture of lithium-ion batteries and improving zinc-bromide flow batteries to experimenting with new energy dense element composites for batteries. The takeaway here is that even though we do not have an answer right now, we do have thirty+ potential answers, or even partial answers that can be utilized in the future to meet our energy storing needs.

If there are any battery innovations you are most excited about, leave a comment down below to keep the conversation going.